Protests against Lithium Mining in Serbia: The Present and the Past

Zuzana Šmilňáková

On July 17, 2024, the Executive Vice-President for the European Green Deal, Interinstitutional Relations and Foresight of the European Commission, Maroš Šefčovič, signed a Memorandum of Understanding between Serbia and the European Union with Serbia’s Minister of Mining and Energy, Dubravka Đedovič Handanović. The signing of the memorandum launched a strategic partnership between the EU and Serbia, focusing on sustainable raw materials, battery value chains, and electric vehicles. German Chancellor Olaf Scholz, present in Belgrade at the time of the signing, remarked, ‘It is important that such a decision was taken today. It increases resilience and promotes the industry.’ How did Serbia become the EU’s hope for a greener future?

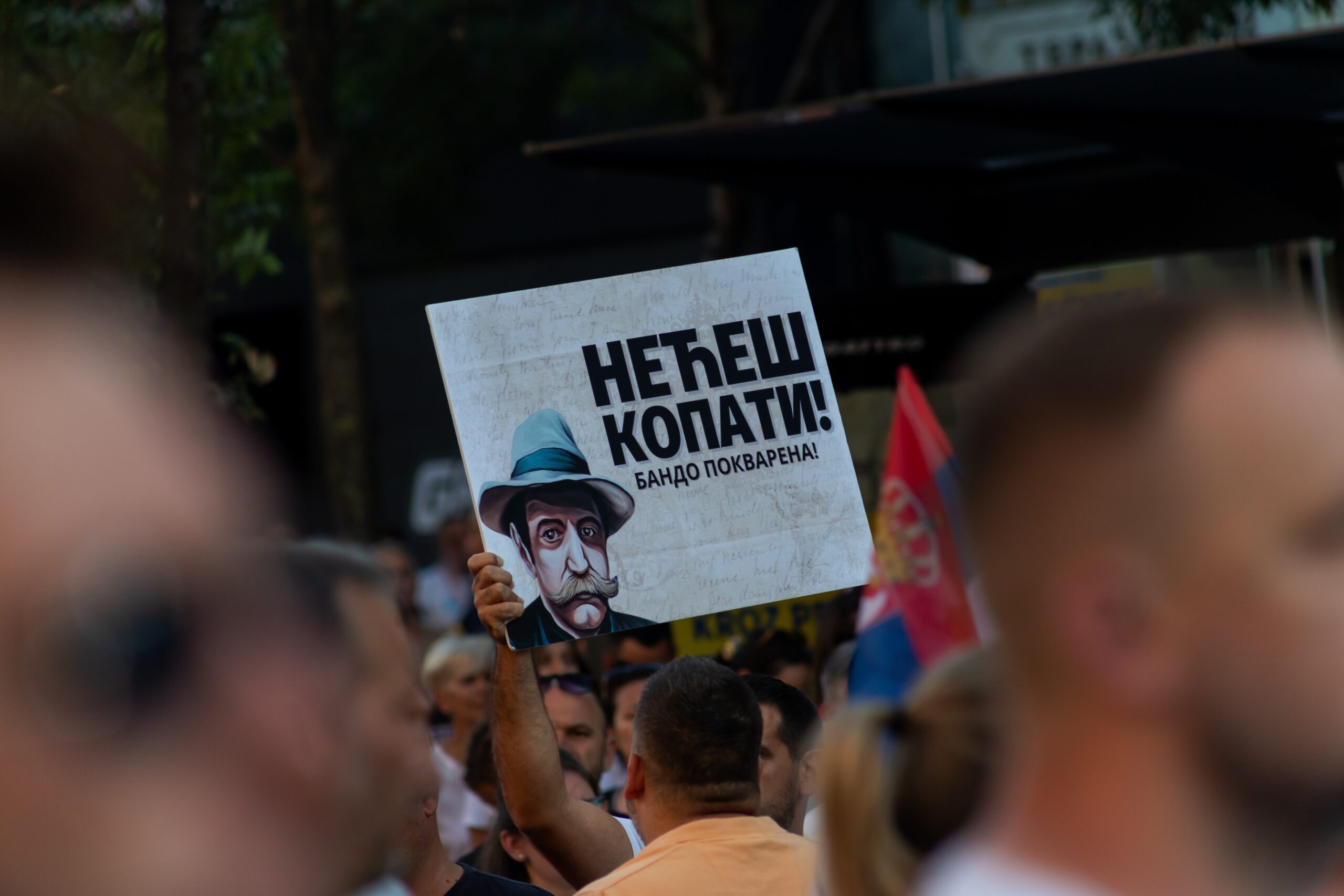

For many Serbians, however, this strategic partnership greenlighted the opening of the controversial lithium and boron mines in Western Serbia. The critics of the mining project responded with significant protests in the Serbian capital, starting in late July. Protests were generally calm until they culminated in a blockade of one of Belgrade’s train stations at the beginning of August. There, protesters clashed with law enforcement, and three have been arrested. This event marked a high point of demonstrations as Serbia’s Interior Ministry reported that the number of protestors reached between 24,000 and 27,000 people, and based on estimates from the international media, the figures might be higher. This was not the first time the activists mobilised the public against lithium and boron mining. The issue has been dividing the Serbian public for at least two years now. What is the past and the present of the Serbia’s lithium mine?

The EU’s Need for Critical Raw Materials

The EU committed to becoming climate-neutral by 2050, a goal that aligns with its overall strategy of fighting climate change called the European Green Deal. Since the EU aims to produce net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, it must decarbonise its economy as soon as possible. However, switching to renewable energy sources requires tons of the so-called ‚critical raw materials‘ currently mined primarily outside the EU, predominantly in Chile, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Australia, and China, among others. The EU acknowledged its vulnerability stemming from the lack of its own critical materials sources and set goals for building up its domestic mining capacities in the European Critical Raw Materials Act signed in 2023.

Discovery of the Serbian ‚Jadarite‘

Serbia’s current importance in overcoming the EU’s reliance on non-European lithium-exporting countries, most importantly Chile, began to take shape twenty years earlier. During the 1990s, geologists from Belgrade’s Faculty of Mining and Geology conducted several studies on mineral composition at the Jadar River Valley in Western Serbia. At the turn of the millennium, the faculty forged relations with foreign investors interested in mining exploration, namely the British-Australian mining company Rio Tinto. Serbia’s subsidiary of Rio Tinto was established in 2001, with Nenad Grubin, a former research assistant at the faculty, becoming its first director. In 2004, a team of four geologists, including Grubin, finally discovered a mineral consisting of borates and lithium, nicknamed Jadarite.

Both boron, which is found in nature in the form of borates, and lithium are recognised as crucial for the EU’s green transition under the European Critical Raw Materials Act. While lithium is needed to produce batteries for electric vehicles crucial for the EU’s decarbonisation, boron is used in wind turbines, which have become an important source of clean energy. Jadarite, therefore, represents a unique combination of critical raw materials, rarely found in nature in great amounts. Rio Tinto estimates that Serbia’s mines could produce 58,000 tons of lithium annually, which should suffice for 1,1 million electric vehicles. In other words, Serbia is predicted to become one of the world’s top ten countries producing lithium, which could significantly help the EU reach its targets for domestic mining capacities.

The Serbian Government’s Cooperation with Rio Tinto

After the successful discovery of the unique Jadarite, Rio Tinto was granted a permit for geological exploration, which has been renewed multiple times both by the pre-2012 Serbian governments and the successive governments led by the Serbian Progressive Party since 2012. In 2017, the Government of Serbia and Rio Tinto signed a Memorandum of Understanding on implementing the Jadar mining project. In 2020, the preliminary geological exploration ended according to Rio Tinto, therefore, the company sought to obtain the necessary permits to start the mining. During this time, the government of Serbia adopted a Spatial plan for the special purpose area that addressed legal issues to allow lithium mining in Jadar Valley. Alongside the plan, the government also introduced amendments to the Law on Expropriation and the Law on Referendum and People’s Initiative.

Mass protests against mining in 2021

At this time, the local activist groups from Western Serbia that were fighting against lithium mining captured the attention of a wider public in the country. In their understanding, lithium mining posed a major ecological threat to the area. They argued that chemicals needed to extract lithium, such as sulphuric acid, might contaminate rivers and land in an inhabited area.

The first wave of mass protests in November 2021 called against adopting the proposed amendments to the laws for fear of their misuse. More protests ensued, with protesters blocking off the roads and bridges in an attempt to mobilise people against the lithium mining project. The activists were quick to frame the issue in a transnational manner, thus gaining support from a global network of environmental activists. Representatives of the environmental organisations from Chile, Spain, Portugal, and Germany supported their Serbian counterparts.

The government initially refused to give in to the demands of protesters, who were pushed back by law enforcement. Prime Minister Brnabić accused them of being funded by foreign organisations, while the former Minister of Mining and Energy, Zorana Mihajlović, called activists‘ environmental concerns false. Throughout the series of mass protests, the government maintained its line of argumentation, claiming that the project would greatly benefit the country thanks to the planned foreign direct investments.

Notwithstanding the governmental attempts to delegitimize protesters’ demands, the mobilization campaign against mining alarmed enough Serbians, so the government was forced to withdraw the amendments to the Law on Expropriation and the Law on Referendum and People’s Initiative in December 2021 and revoke the Spatial plan in January 2022.

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Situation after the Revocation of the Jadar Project

A red light on the development of the mining site from the Government of Serbia at the beginning of 2022 did not prevent Rio Tinto from continuing to buy up the land around Jadar River Valley. According to the Balkan Investigative Reporting Network, which analysed data from Serbia’s state cadastre, Rio Tinto spent 1,2 million EUR on 5,78 hectares of land between 2022 and 2023. Furthermore, the company launched a program devised to provide financial grants to local businesses in Loznica, a city close to the proposed mining site. Amid the public worrying about the possibility of the project’s revival, Prime Minister Ana Brnabić repeated multiple times that the project would not be reinvigorated.

Several of the environmental groups that participated in the protests were able to turn their recognition into votes in the parliamentary elections. The groups ‘Together for Serbia’, ‘Let’s not drown Belgrade’, and the ‘Ecological Uprising’ formed a coalition called Moramo (We have to) that managed to enter the Serbian National Assembly with 4.7% of the popular vote in the 2022 elections. Furthermore, the leader of the activist group Kreni-Promeni, which initially spearheaded demonstrations, Savo Manojlović, was elected to the City Assembly of Belgrade in the 2024 elections.

Current Protests

On 11 July 2024, the Constitutional Court of Serbia ruled that the previous governmental revocation of the spatial plan for mining had been unconstitutional. In a matter of a few days leading up to the signing of the memorandum between Serbia and the EU, Serbian authorities further adjusted the legal framework to allow for the revival of the mining project. After the memorandum had been ceremonially signed during the Serbian Critical Raw Materials Summit on 17 July 2024, environmental groups that organised protests in late 2021 mobilised again.

From the single-issue local activist groups such as Ne Damo Jadar, Marš sa Drine, Zaštitimo Jadar i Rađevinu to the ecological groups that work on a national level and have a wider agenda, such as the aforementioned Kreni-Promeni, they all quickly mobilised their structures during the summer. Local protests in cities near Jadar Valley and gatherings in Belgrade have become routine in the country over the summer of 2024.

Photo: Shutterstock.com

Rio Tinto’s Current Plans

After twenty years of exploratory studies, Rio Tinto is determined to start with the mining operations. According to the company’s manager for Serbia, Chad Blewitt, the company has spent over 600 million USD on the project so far. After the backlash in 2021 and 2022, the company shifted its marketing strategy for the project and started holding information sessions for the local communities likely to be affected by the mining. Furthermore, the company issued environmental impact assessments to prove its claims that the Jadar Project will not harm the region’s environment.

The citizens of the Jadar Valley fear the possible damage to their agricultural land. Rio Tinto addressed these concerns by promising to build an underground mine instead of an open pit mine. Moreover, the company promised to adhere to the highest environmental standards and urged Serbians not to judge its reliability according to its past scandals, which included the destruction of the sacred Aboriginal site in Australia and large-scale environmental damage in Papua New Guinea. Besides hosting frequent information sessions and investing money in local businesses, Rio Tinto provides information on the public’s most pressing concerns on its website, where it, for instance, claims no damage will be done to the underground water in the area.

In September 2024, Rio Tinto’s CEO, Jakob Stausholm, reiterated that the company should have done more to inform the public about the project from the outset. In his view, Rio Tinto is currently facing an organised disinformation campaign in Serbia.

Conclusion

In June 2024, Serbia’s President, Aleksandar Vučić, stated that the mine would become operational in 2028 at the earliest. Serbia’s Minister of Mining and Energy, Dubravka Đedovič Handanović, announced in August 2024 that the licensing process for the Jadar Project can take up to two years, she added that the speed of the process is presently in the hands of the government. Given the intense support for the Jadar Project from the Serbian government and the EU, it is hard to imagine how the project can be stopped. With the next parliamentary elections scheduled for 2027, the mine construction might be in full swing by the time the opposition has a chance to intervene.

As the struggle against mining becomes framed as a struggle for Serbian sovereignty, more people are swayed toward Euroscepticism in an already heavily Eurosceptic country. The issue has impacted the image of the EU, even among the country’s pro-Western population. It is unclear how this will change Serbia’s accession process to the EU in the long run. With their eyes set on the ultimate prize, the money from the Jadarite, Vučić’s government might become even tougher on the environmental groups in the upcoming years. The EU must ensure the activists are treated with respect to their right to protest.

Sources:

- Alejandro González and Bart-Jaap Verbeek, SOMO, 15 May 2024, The EU’s critical minerals crusade: How the EU trade policy on raw materials deepens the environmental and inequality crises, https://www.somo.nl/the-eus-critical-minerals-crusade/

- Balkan Green Energy News, 13 June 2024, Rio Tinto releases draft environmental impact assessments for Jadar Project, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/rio-tinto-releases-draft-environmental-impact-assessments-for-jadar-project/

- DW, 19 July 2024, EU, Serbia sign key lithium deal, https://www.dw.com/en/eu-serbia-sign-key-lithium-deal/a-69712085

- European Commission, 16 March 2023, European Critical Raw Materials Act, https://commission.europa.eu/strategy-and-policy/priorities-2019-2024/european-green-deal/green-deal-industrial-plan/european-critical-raw-materials-act_en

- Igor Todorović, Balkan Green Energy News, 10 July 2022, Jadar Declaration unites activists in global resistance against lithium mining, https://balkangreenenergynews.com/jadar-declaration-unites-activists-in-global-resistance-against-lithium-mining/

- Ivana Sekularaća and Aleksandar Vasović, 9 August 2024, Rio Tinto’s Serbia lithium project could take two years to approve, minister says, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/rio-tintos-serbia-lithium-project-could-take-two-years-approve-minister-says-2024-08-09/

- Luka Šterić, The Belgrade Centre for Security Policy, October 2023, A Driver of Green Transition or a Colonial Tailings Dump: Political Discourse on the Jadar Project, https://doi.org/10.55042/YRGR5169

- Milica Stojanović, Balkan Insight, 11 July 2024, Serbian Court Ruling on Scrapped Lithium Mine Dismays Environmentalists, https://balkaninsight.com/2024/07/11/serbian-court-ruling-on-scrapped-lithium-mine-dismays-environmentalists/

- Milica Stojanović, Balkan Insight, 19 July 2024, European Union Agrees Controversial Lithium Mining Project with Serbia, https://balkaninsight.com/2024/07/19/european-union-agrees-controversial-lithium-mining-project-with-serbia/

- Milica Stojanović, Balkan Insight, 13 August 2024, Serbia Frees Activists Arrested at Anti-Lithium Mining Demonstration, https://balkaninsight.com/2024/08/13/serbia-frees-activists-arrested-at-anti-lithium-mining-demonstration/

- Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, 15 September 2024, Rio Tinto CEO Says ‚Well-Organized‘ Disinformation Targeting Serbian Lithium Project, https://www.rferl.org/a/serbia-lithium-tinto-stausholm-mine/33120768.html

- Reuters, 7 October 2024, Serbia’s parliament debates ban on lithium mining, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/serbias-parliament-debates-ban-lithium-mining-2024-10-07/

- Rio Tinto, Concerns and Facts about the proposed Jadar Project, https://riotintoserbia.com/en/jadar-project/concerns-and-facts

- Rob Schmitz, NPR, 23 August 2024, A lithium mine in Serbia could rev up Europe’s e-vehicles, but opposition is fierce, https://www.npr.org/2024/08/23/nx-s1-5081517/rio-tinto-lithium-serbia-europe-ev-vehicles-battery-supply-chain

- Sasa Dragoljo, Balkan Insight, 13 April 2022, ‘It’s [Not] Over’: The Past, and Present, of Lithium Mining in Serbia, https://balkaninsight.com/2022/04/13/its-not-over-the-past-and-present-of-lithium-mining-in-serbia/

- Sasa Dragoljo, Balkan Insight, 23 February 2023, Rio Tinto Spends Million Euros on Serbian Land since Mine Cancellation, https://balkaninsight.com/2023/02/23/rio-tinto-spends-million-euros-on-serbian-land-since-mine-cancellation/

- Tibor Moldvai, Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 18 January 2022, The Rio Tinto Controversy in a Nutshell, https://rs.boell.org/en/2022/01/18/rio-tinto-controversy-nutshell

- Tibor Moldvai and Katja Giebel, Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 2 August 2024, Lithium Mining in Serbia: “An Open and Productive Debate Is Not Possible”, https://rs.boell.org/en/2024/08/02/lithium-mining-serbia-open-and-productive-debate-not-possible

Zuzana Šmilňáková is an Intern at the Strategic Analysis Young Leaders Programme

Disclaimer: Views presented here are those of the author solely and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Strategic Analysis

Contact us