Dissemination of pro-Russian narratives via media in North Macedonia

Kateřina Sajdová

North Macedonians aren’t one of Russia’s staunchest supporters, and Russian interest in the country itself is not among the most notable in the Western Balkans. Nevertheless, Moscow does not appear to be reluctant to implement unique, suitable information meddling along with additional kinds of influence within the country to keep it out of European integration. It is important to be aware of it, even though North Macedonia is not currently a Kremlin’s interest hotspot.

The Western Balkan region as a whole is vital for Moscow, not only because Russia intends to dominate the post-communist Eastern bloc over the West but also because of its geostrategic location between the Black Sea and the Adriatic Sea and close to the Middle East. Furthermore, Russia aims to influence identity politics, religious connections, and economic interests in the region while using a variety of assets to project soft power, including media outlets, the Orthodox Church, businesses, motorcycle gangs, and others. During the 1990s, Russia’s influence in the area was negligible, as NATO and the United States dominated. However, in the 2000s, things changed. Following the September 11 attacks, NATO’s aims broadened, and its focus switched to counterterrorism. As a result, responsibility for the region devolved mostly on the European Union, which lacked a clear and strong strategy towards the Western Balkans. Russia took the chances and focused on the Western Balkan area more thoroughly.

In recent years, the renewed Russian interest in North Macedonia and the Western Balkans has been primarily driven by “enlargement fatigue” within the EU and the Western push for Western Balkan countries to take a firm stance against Russia due to its aggression in Ukraine. This Western pressure, however, often fails to recognise the complex dynamics of the region. While Balkan history and politics are not inherently pro-Russian, they tend to be more anti-Western. The insistence on opposing Russia might backfire.

Even though four out of six Western Balkans countries, including North Macedonia, are now in the EU accession negotiations, the process of integration is too slow and is developing into “enlargement fatigue”. This creates a gap for Russia and China to disseminate their influence by taking advantage of the economic and European enlargement stagnation. The growing scepticism can be seen on Balkan Barometer from 2023, showing the continuing trend from 2022 of a decrease of positive viewing of EU membership by another 1% (already a 3% drop since 2021, until then, the support was rising). North Macedonia is the second with the lowest percentage of supporters after Serbia. 34% of the Western Balkan population still believes that the integration will happen until 2030 (3% less than in 2022), and another third goes for 2035. But the evidence that the trend of “enlargement fatigue” is real, is supported by the percentage rise to 24% of Western Balkans citizens who think that the integration will never happen. This growing scepticism towards the enlargement and the tiredness of how slow the process is developing creates an attractive gap for non-Western parties to intervene using the disillusionment of the Western Balkans population.

North Macedonians have also been disappointed with the European Union on a few occasions besides the slowness of the process itself. Greece’s denial of entry without a name change, Bulgaria’s veto because of disagreement over the constitutional status of the Bulgarian minority, and the Union’s lack of understanding for the North Macedonian side in both cases. Attitudes like these contribute to the establishment of an ideal environment for spreading anti-West narratives intermingled with pro-Russian agenda bearers. It’s essential to distinguish between anti-West and pro-Russian sentiments, as they are not always equivalent, especially in the Balkans. As Vuk Vuksanović from Belgrade Security Forum stated in the interview : “Russia is not popular in the region because of what it is, but because of what it is not – and that is not being the West” (Kolovska, 2024). A considerable amount of the Western Balkan s population, including North Macedonians, perceives Russia as a victim of the West rather than an aggressor. Another significant factor is that a GLOBSEC survey from 2021 indicated that 65% of North Macedonian respondents identify with the narrative of Russia as their Slavic brother.

This article will look closely at three examples out of the wide range of the carriers of pro-Russian discourses in the North Macedonian infosphere because even a seemingly harmless magazine aisle in North Macedonia may contain a secret motive. Pro-Russian narratives are invading the nation via unusual avenues such as alternative medicine journals, as well as more traditional methods such as dissemination of manipulation via the Orthodox Church and Russian embassy online activities. While some messages are obvious, others are expertly camouflaged. Russia’s never-ending fight against Western integrations persists, subtly threading its influence through various channels, perpetuating its agenda covertly.

The Russian Embassy’s online engagement

Russian embassies throughout the whole world are recognised for their significant level of malign activities. The Western Balkans is not an exception, but the engagement in particular states differs. The Russian Federation Embassy in the North Macedonian capital, Skopje, stands out as a thriving centre of involvement. Their online presence on Facebook is especially fascinating, with an average of five postings a day, according to a study from 2023 monitoring two previous years . Even after that the number of Facebook posts remains high. For example, in June 2024, the number of posts per day reached approximately four. The only higher average posting in the mentioned region on Facebook, according to Centre for the Study of Democracy research, can be seen from the Russian Embassy in Romania, with about ten Facebook postings each day.

Since 2008, when Greece blocked North Macedonia’s NATO entry, the Russian Embassy in Skopje has been a source of pro-Russian narratives and propaganda. This impact goes beyond being a post sharing a simple public message, as indicated by a 2017 briefing produced for the director of the Macedonian Administration for Security and Counterintelligence, Vladimir Atanasovski. The document mentions it as a part of the Russian Federation’s strategy to isolate North Macedonia from the influence of the West.

Both the official embassy website and its Facebook page remain highly active, even during the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with only a little less engagement a few months after its start on February 24, 2022. This sustained internet presence demonstrates the embassy’s dedication to preserving influence and communicating with the Macedonian people. The embassy maintains its presence to keep disseminating pro-Russian attitudes in North Macedonia by strategically utilising social media channels.

„Putin’s regime has strategically employed the Russian Orthodox Church as a tool of soft power in foreign countries. Under the guise of Orthodox Christianity and narratives of Slavic brotherhood, the Kremlin establishes connections with believers across the Western Balkans, including North Macedonia.“

The Russian Orthodox Church

Putin’s regime has strategically employed the Russian Orthodox Church as a tool of soft power in foreign countries. Under the guise of Orthodox Christianity and narratives of Slavic brotherhood, the Kremlin establishes connections with believers across the Western Balkans, including North Macedonia. This strategy also provides a great platform for Russian oligarchs like Konstantin Malofeev, who operates the St. Basil the Great Charitable Foundation, primarily from Serbia. Malofeev, via his foundation, promotes pan-Slavic civilisation ideals, opposing Western influence and occasionally resorting to conspiracy theories to sway public opinion.

Following the Russian invasion starting in February 2022, numerous Russian diplomats and agents were expelled from various nations, prompting the Kremlin to utilise more covert methods. In Orthodox countries, this often involves infiltration through local churches. And North Macedonia is not an exception.

In June 2023, the former President of North Macedonia, Stevo Pendarovski, revealed a collaboration between high-ranking members (excluding the head) of the North Macedonian Orthodox Church (MOC) hierarchy and the Russian Secret Service. This also explains the reluctance within the Macedonian Church to pursue recognition from the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople, with its non-hidden pro-Western routing.

The Russian influence can also be shown in the case of Marjan Nikolovski, a respected editor and journalist who owns the “Religija.mk” portal, who now faces scrutiny from the Ecclesiastical Court of the Macedonian Orthodox Church – Archdiocese of Ohrid (MOC-OA). He stands accused of inciting hatred among believers and criticising the Synod, the MOC’s leadership. Nikolovski’s allegations center on exposing Russia’s pervasive influence in Macedonia through the Church, particularly involving three bishops in the media. He argues that despite Moscow previously branding the MOC-OA as schismatic, Russian authorities exploit emotional ties associated with the Church’s identity to manipulate Macedonian Church interests.

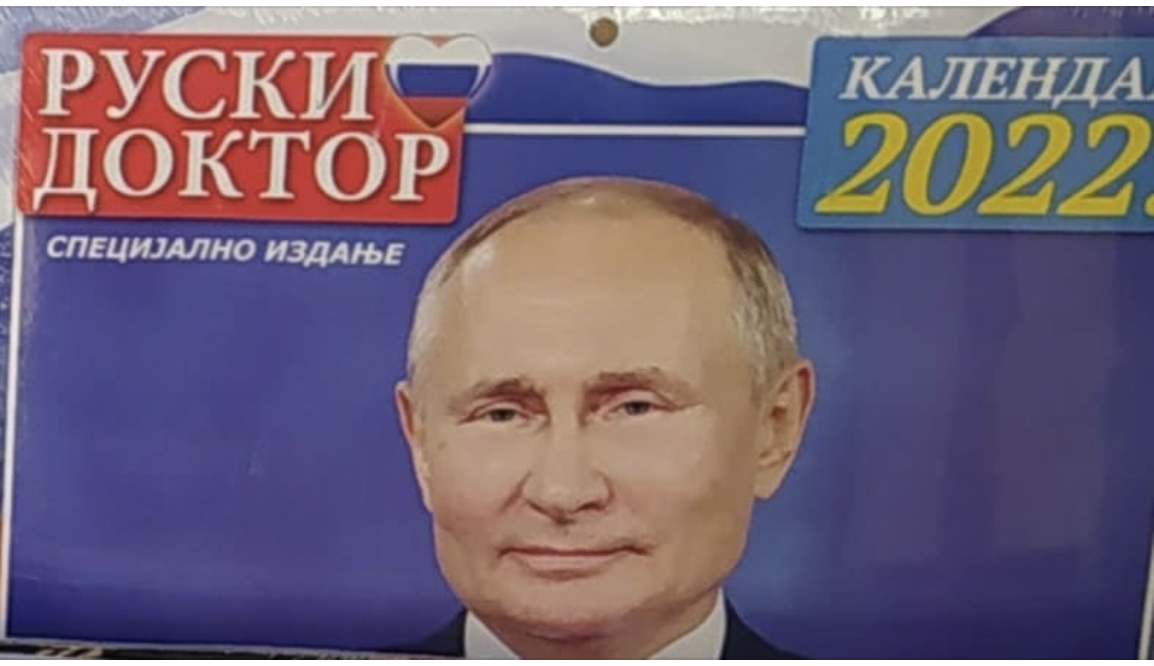

Photo: You Go Slavia, Facebook page- https://www.facebook.com/groups/yougoslavia/posts/1105731356878858/

Alternative medicine magazines

In the Republic of North Macedonia, several magazines focusing on alternative medicine show clear connections to Russia. These publications, namely Russian Herbalist, Russian Medicine, and Ruski Doktor (Russian Physician),present health and medical topics using non-conventional advice, consistently framing them within a Russian context. As an example, Ruski Doctor, uses a visual colour scheme evocative of the Russian flag and includes representations of the flag itself – a Russian flag shaped as a heart appears in the magazine’s title. Moreover, some issues even showcase Vladimir Putin on their covers and calendars. To deepen the connection to Russia, periodicals use the motto “Russian advice for good health!” or make allusions to Russian medical/alternative procedures that improve lives. The campaign appears to be intended to promote good impressions of Russia. Additionally, the publisher declines to take responsibility for the truthfulness of articles or marketing remarks, which are written in small letters on every piece of Ruski Doktormagazine.

Regardless of the fact that it is no longer officially published in Macedonian, the Serbian version continues to be printed and distributed around the country. Belgrade based “Colour Media International” publishes this magazine also in Croatian and Slovenian, yet only the edition in Serbian can be bought in North Macedonia, as is the case in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro. The first thing to be aware of is the cost, which happens to be the lowest compared to other Macedonian language paper media with similar proportions in the country. Furthermore, when compared to other nations where the magazine is available, this particular issue of Ruski Doktor, distributed in North Macedonia, has the lowest price. It’s even lower than in Serbia, the original-distributing country. Given the topic at stake and the price tag, the elderly population appears to serve as the targeted audience.

Conclusion

Although North Macedonia is not among Russia’s primary areas of interest in the Western Balkans, Moscow continues to actively pursue its influence strategy in the country. Russia’s regional aspirations are motivated by both geopolitical concerns and a strategic desire to resist Western influence and European integration initiatives. The position of the Western Balkans, due to its proximity to the Black Sea, Adriatic Sea, and the Middle East, makes it a critical area for Russia’s foreign policy objectives.

Examples such as the propagation of Russian-themed alternative medicine magazines, the Russian Embassy’s active online presence, and the infiltration of the Russian Orthodox Church illustrate only some of the diverse methods Russia employs to maintain its influence in North Macedonia. These efforts are part of a larger strategy to undermine Western integration and bolster Russian soft power in the region.

Understanding these dynamics is crucial for addressing the challenges posed by Russian influence and supporting the Western Balkans’ path towards European integration. The region’s complex political landscape requires nuanced and informed approaches to counteract external meddling and foster stability and progress. It is necessary to separate the resistance against Russian influence in the Western Balkans from the rest of Europe as the complexities differ.

Sources:

- Angel Dimoski, MIA, “Presentation of Study on Russian Propaganda Influence and Disinformation in North Macedonia”, https://mia.mk/en/story/presentation-of-study-on-russian-propaganda-influence-and-disinformation-in-north-macedonia

- Branislav Stanicek and Anna Caprile, European Parliamentary Research Service, “Russian Influence in the Western Balkans: Enlargement Challenges”, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/747096/EPRS_BRI(2023)747096_EN.pdf

- Connor O’Kelley, CSD, “Flash Report: Russian Embassy Disinformation”, https://csd.bg/fileadmin/user_upload/projects/files/Flash_Report_Russian_Embassy_Disinfo_v1.pdf

- Engjellushe Morina and Andrew Wilson, European Council on Foreign Relations, “Russia, Ukraine, and the Orthodox Church: Where Religion Meets Geopolitics and War”, https://ecfr.eu/article/russia-ukraine-and-the-orthodox-church-where-religion-meets-geopolitics-and-war/

- Euronews Albania, “Study Reveals Russian Influence Through Propaganda in North Macedonia”, https://euronews.al/en/study-reveals-russian-influence-through-propaganda-in-north-macedonia/

- Facebook page of the Russian Embassy in North Macedonia, https://www.facebook.com/RussianEmbMKD/

- GLOBSEC, “Image of Russia: Mighty Slavic Brother or Hungry Bear Nextdoor?”, https://www.globsec.org/sites/default/files/2021-04/Image-of-Russia-Mighty-Slavic-Brother-or-Hungry-Bear-Nextdoor-spreads.pdf

- Goran Lefkov, Truthmeter.mk, “The Russian Embassy in Skopje – Main Diplomatic Internet Spammer in North Macedonia”, https://truthmeter.mk/the-russian-embassy-in-skopje-main-diplomatic-internet-spammer-in-north-macedonia/

- Goran Lefkov, Vistinomer.mk, „Руски агенти во мантија?“, https://vistinomer.mk/ruski-agenti-vo-mantija/

- Harun Karčić, Berkley Center, “Russia’s Influence in the Balkans: The Interplay of Religion, Politics, and History”,https://berkleycenter.georgetown.edu/posts/russia-s-influence-in-the-balkans-the-interplay-of-religion-politics-and-history

- Матеј Тројачанец, Truthmeter.mk, “Interview with Nikolovski: Russian Church Players in MOC-OA Imposed Fake Public Topics”, https://truthmeter.mk/interview-nikolovski-russian-church-players-in-moc-oa-imposed-fake-public-topics/

- Meta.mk, “Media Narratives About EU as a Factor of Increased Russian Influence in North Macedonia”, https://meta.mk/en/media-narratives-about-eu-as-a-factor-of-increased-russian-influence-in-north-macedonia/

- Meta.mk, “The Social Media as a Lever for Spreading Authoritarian Propaganda”, https://meta.mk/en/the-social-media-as-a-lever-for-spreading-authoritarian-propaganda/

- Meta.mk, “Emotional Ties and Propaganda: The Russian Soft Power in the Balkans”, https://meta.mk/en/emotional-ties-and-propaganda-the-russian-soft-power-in-the-balkans/

- Metamorphosis Foundation, Global Voices, “Russian Influence in North Macedonia is Particularly Present Around Key Political Events, Disinformation Researcher Says”, https://globalvoices.org/2022/02/18/russian-influence-in-north-macedonia-is-particularly-present-around-key-political-events-disinformation-researcher-says/

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation, https://mid.ru/ru/foreign_policy/belye_knigi/

- Vesna Kolovska, Meta.mk, “Emotional Ties and Propaganda: The Russian Soft Power in the Balkans”, https://meta.mk/en/emotional-ties-and-propaganda-the-russian-soft-power-in-the-balkans/

- Yordan Tsalov, Bellingcat, “Russian Interference in North Macedonia: A View Before the Elections”, https://www.bellingcat.com/news/uk-and-europe/2020/07/04/russian-interference-in-north-macedonia-a-view-before-the-elections/

Kateřina Sajdová is a student of Security and Strategic studies at Masaryk University in Brno.

Disclaimer: Views presented here are those of the author solely and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Strategic Analysis.

Contact us